The War That Built the City: Lessons in Resilience from Wartime London’s Law Firms

Kateryna Andreieva, Business Development & PR Director, Ilyashev & Partners Law Firm

The experience of British law firms in wartime London offers a powerful historical lens through which to view our own professional transformation. Amid destruction, uncertainty, and national mobilisation, London’s legal community learned to preserve integrity, continuity, and trust – the same values now being tested in Ukraine’s legal market.

The Second World War radically transformed life in the British capital. General mobilisation in the United Kingdom began in September 1939, immediately after the declaration of war on Germany. It was compulsory for men aged 18 to 41 (later extended to 51), and from December 1941 – for the first time in the country’s history – women were also called up for war service, both in the armed forces and in industry.

While the British government introduced the Schedule of Reserved Occupations in September 1939 to exempt essential civilian workers from military service, the legal profession was not formally included in the list[1]. Solicitors and barristers were not regarded as indispensable to the war economy in the same way as engineers, miners, or doctors. Nevertheless, some lawyers were individually retained in civil or judicial posts deemed critical to maintaining the administration of justice – including roles in government departments, military tribunals, and the Treasury Solicitor’s Office. The majority, however, were subject to mobilisation like other citizens, and many volunteered even before being called up.

As a result, a significant number of junior lawyers and even partners from London firms left to serve in the armed forces or in government institutions. According to the Law Society’s wartime report[2], 7,202 solicitors and 2,253 articled clerks served in the armed forces. The Roll of Honour preserved the names of 111 solicitors who lost their lives[3]. Solicitors earned 1,278 individual wartime decorations, including 22 Distinguished Service Orders, 131 Military Crosses, and 159 Members of the Order of the British Empire – extraordinary numbers for a civilian profession.

Yet heroism was not confined to those who went to the front. It was displayed daily by colleagues who kept the offices running.

How the Offices Functioned During the War

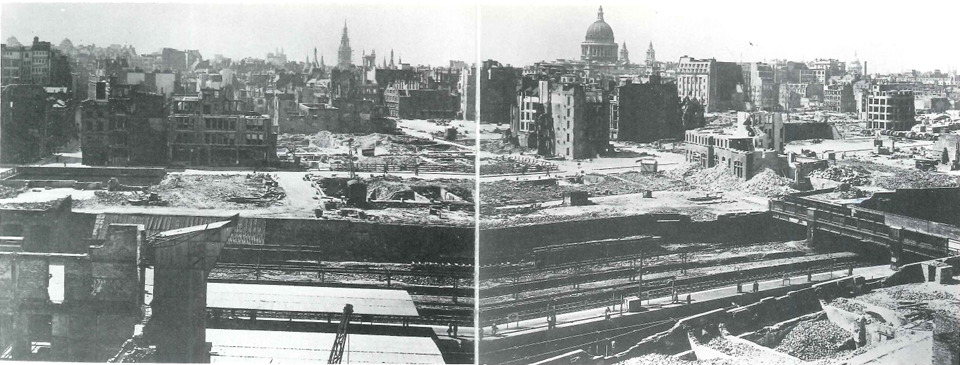

Between September 1940 and May 1941, London came under sustained attack in a series of 57 air raids known as the Blitz.

During the night of 29-30 December 1940, in one of the most dramatic raids of the Blitz – later known as the Second Great Fire of London – around 130 German bombers dropped nearly 100,000 incendiary and high-explosive bombs on the City. More than 1,500 fires broke out. Over 160 civilians and 14 firefighters were killed, and several hundred more were injured.

Five months later, in the night of 10-11 May 1941, London suffered its deadliest air raid of the Blitz. According to the UK Parliament records, 505 German bombers dropped over 700 tons of high explosives and 86,000 incendiaries, killing 1,364 people and seriously injuring 1,616.

The bombings destroyed entire districts of London and thousands of buildings, including the offices of law firms in the City. Many lawyers and clerks walked for hours each day to reach their workplaces – often unsure whether the building would still be standing. Public transport was unreliable, although the Underground continued to operate for much of the time. A journey that had taken an hour before the war could now take half a day.

The conditions in which firms operated during the Second World War were often dire. Travers Smith’s office – then known as Travers Smith, Braithwaite & Co. – though never directly hit by enemy bombs[4], was left in a deplorable state: its windows shattered by nearby explosions, rooms coated in dust and debris, and files buried under layers of grime. Staff learned to adapt, wearing their coats indoors through the winter and protecting documents with whatever improvised materials they could find. Over time, these hardships became an accepted part of daily professional life.

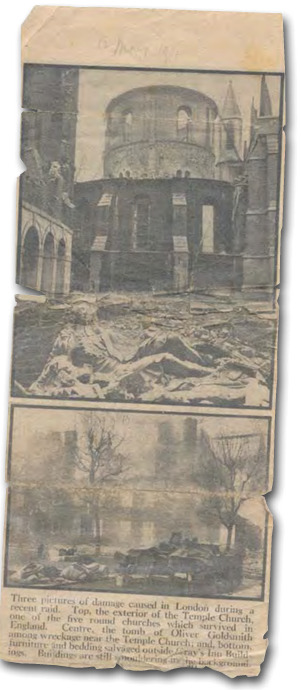

When the Second World War began, several members of Bird & Bird’s staff were called up for military service, leaving behind half-empty offices and an uncertain future. Yet the firm’s partners refused to let the war sever their connection with those who served: salaries continued to be paid throughout active duty[5]. Then came the Blitz – in 1941, the firm’s historic home at 5 Gray’s Inn Square was reduced to rubble in a night of bombing. Amid smoke and falling masonry, its remaining staff salvaged what they could and, within days, resumed work from temporary rooms nearby.

In December 1940 Linklaters & Paines’ City offices at 2 Bond Court, Walbrook, were reduced to ashes. Partners and clerks worked through nights on fire-watching duty, rescuing documents from the ruins. Within weeks, the firm had secured temporary offices on Cannon Street – and against all odds, resumed practice, carrying on its work in the midst of a city still smouldering.

By June 1941, access to the remains of the strong-room was restored, and soaked, half-burnt files were recovered and reconstructed from client copies[6]. Despite the destruction of its offices, Linklaters & Paines also kept paying the salaries of all staff on active service and maintained a functioning partnership throughout the war. Even with profits halved, partners agreed in 1941 to preserve full pay for enlisted employees.

Theodore Goddard & Co (since 2003 – Addleshaw Goddard) faced one of the heaviest blows of all. In 1941, its office at 10 Serjeants’ Inn was hit directly during a bombing raid and completely destroyed, along with client files and archives[7]. Yet the firm continued: it relocated and rebuilt its practice.

Macfarlanes, then known as Neish, Howell & Haldane, also suffered wartime damage and their offices in Watling Street were pulled down as part of a redevelopment project, after suffering from heavy wartime bombing. By the end of the war only two partners remained with the firm, Owen Howell and Craig Macfarlane, but the firm soon began to rebuild by adding another two partners to their ranks.

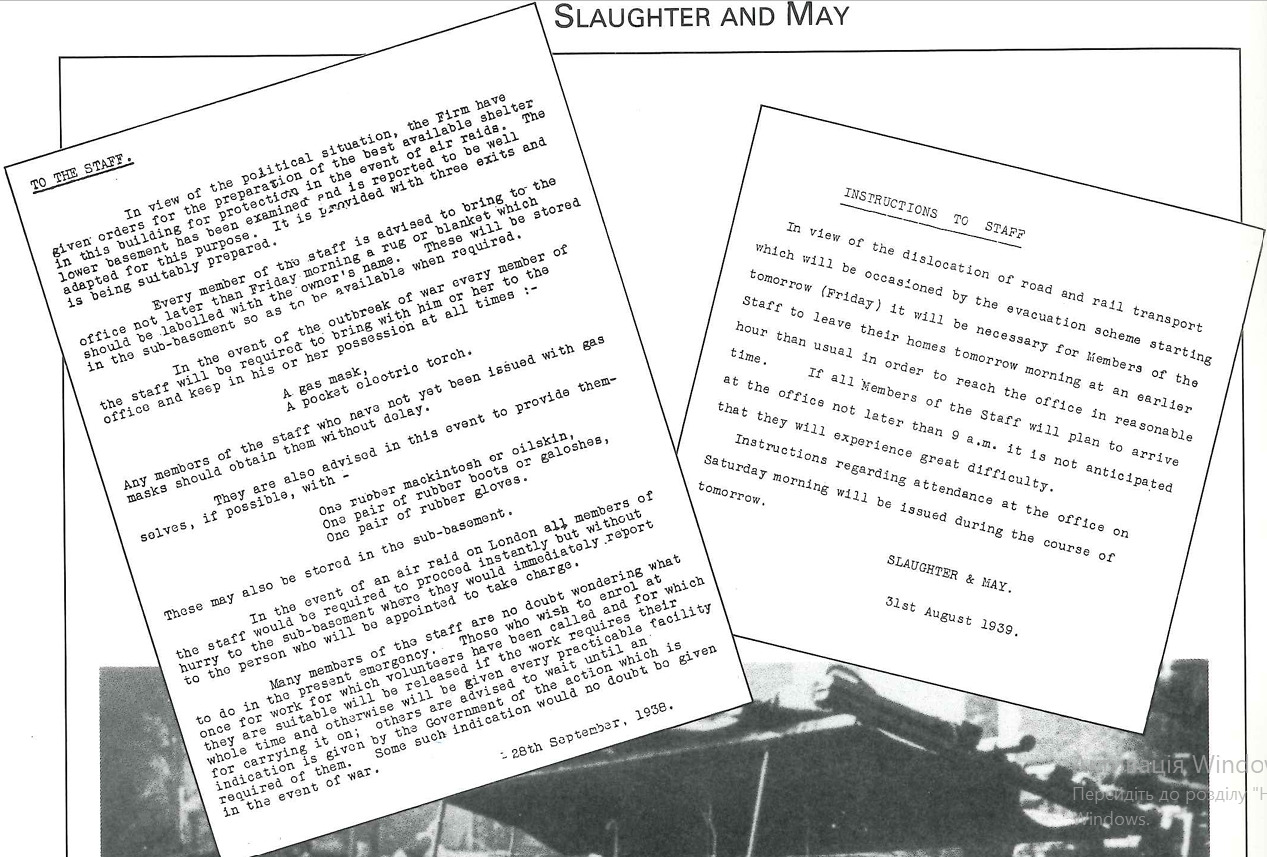

For Slaughter and May, the war years became a test not only of endurance but of spirit. Many partners and staff left for wartime service, including in intelligence roles with the Special Operations Executive. Those who remained kept the office running, sometimes spending nights on fire-watching duty to protect the premises during air raids.

The firm’s base at 18 Austin Friars survived the Blitz, but its surroundings were devastated – most strikingly, the Dutch Church across the street was reduced to ruins in October 1940. Office’s windows were boarded up and staff often worked in cold, dim rooms. Heating was unreliable, coal supplies consisted largely of dust, and rationing extended even to bread. Junior clerks recalled working in their coats and reusing every scrap of paper and envelope[8]. Administrative staff worked in the basement at night, sorting and organizing the delivery of correspondence to clients.

Still, the work of the City firms never stopped – a quiet defiance that kept the rhythm of London’s legal life alive through the darkest days of the war. Amid devastation, shortages, and constant threat, the ability to adapt swiftly and maintain continuity of service became the ultimate test of the profession’s resilience.

How Legal Services Changed During the War

According to Chris Hale, Senior Consultant at Travers Smith, who has worked at the firm since 1983 and became a partner in 1987, the wartime disruption struck at the very heart of the City of London’s legal and commercial ecosystem. “The Second World War caused a major disruption to much of business in the City of London on which Travers Smith then relied, not least because many of those who had worked there went off to fight. Much of the City’s core business declined to a trickle. There was little capital markets, mergers and acquisitions or real estate work,” he recalled.

With law firms at the time being only a fraction of their present size, Travers Smith saw the majority of its lawyers join the armed services – some never returning. What remained was a skeleton staff working under punishing conditions; the office windows blown out early in the war remained unrepaired until after the war ended. “The sort of work the few remaining did had a strong litigation bias… and there was a little non-contentious work for regular clients, again some war related,” Hale added. Yet despite these challenges, he emphasized that the defining legacy of these years was resilience – of both the individuals who kept the firm running and the firm itself, which not only survived but went on to thrive in the post-war era.

The Second World War profoundly transformed the structure and priorities of leading City law firms. Traditional solicitor work – wills, trusts, and conveyancing for private clients – continued, but its relative importance declined. Instead, the legal profession adapted to serve an economy directed toward survival and reconstruction. The demands of government regulation, wartime industry, and financial control systems created new fields of legal work, reshaping firms from private advisers to strategic partners in national administration and commerce.

Across the profession, firms diversified their practices in response to wartime realities. Property and probate matters multiplied as casualties rose, while new advisory needs emerged in taxation, exchange control, contracts, and insurance. Lawyers became increasingly involved in regulatory and compliance work, helping industries interpret and implement emergency economic measures. These activities marked the beginning of a more institutionalised legal profession – one in which practice areas were defined by expertise rather than personal reputation.

Internally, firms introduced procedures designed to maintain continuity under pressure. Typewritten multi-copy correspondence, standardised document checklists, and systematic record-keeping replaced the informal habits of pre-war offices. Wartime scarcity demanded efficiency, and the discipline acquired under these constraints later evolved into modern law firm management.

The war also accelerated a fundamental shift in client base. Firms that had once depended on the landed gentry and private wealth turned increasingly toward commercial and industrial clients – particularly in sectors vital to the war effort such as manufacturing, finance, and technology. This realignment laid the foundations for the modern City firm: internationally connected, commercially oriented, and structurally resilient.

Post-War Reconstruction and the New Economic Reality

In 1945, thousands of solicitors and clerks returned from military service to a nation struggling with economic austerity, rationing, and a severe shortage of skilled staff. Partners worked side by side in shared rooms, rebuilding archives and client networks. The Linklaters’ senior partner at the time described the post-war British economy as a “financial Dunkirk”.

The return to peace brought not prosperity but regulation: currency and trade controls, nationalisation of key industries, and the introduction of new taxation regimes. Firms that had maintained operational discipline and client trust during the war now guided both public and private enterprises through this controlled, highly bureaucratic environment.

Yet scarcity also became a catalyst for innovation. As Britain transitioned from wartime command to peacetime reconstruction, law firms found themselves indispensable to rebuilding the economy.

In many ways, the war had compelled a level of organisation that ultimately made the profession stronger. The social fabric of law also changed. The traditional family partnerships of the interwar years gradually gave way to a new generation of solicitors shaped by wartime pragmatism.

Across the City, professionalism began to outweigh pedigree. The age of the “gentleman solicitor” gave way to an institutional ethos defined by efficiency, expertise, and continuity.

By the early 1950s, the contours of the modern British legal profession were clearly defined: regulated yet entrepreneurial, national in responsibility yet global in outlook. The war had destroyed much – but it had also created the foundations for a new kind of law firm: disciplined, adaptive, and deeply integrated into the machinery of economic recovery.

The Arrival of Foreign Law Firms in London

The post-war decades transformed London from a damaged capital into the world’s leading financial center. Yet for much of the 1950s, the British legal market remained remarkably insular. Strict professional regulations, exchange controls, and immigration rules made it nearly impossible for foreign lawyers to practice English law or even to establish a permanent presence in the City. As a result, the internationalization of London’s legal scene began relatively late.

The first foreign entrants, including Baker & McKenzie, arrived only in the early 1960s. By the early 1970s, a new wave of U.S. firms entered the market – Vinson & Elkins (1971), White & Case (1971), and Shearman & Sterling (1972) – taking advantage of the liberalization of financial regulations and the emergence of the Eurodollar market, which turned London into the hub of global banking.

Among these pioneers, the example of White & Case is particularly revealing. Unlike many of its British counterparts, White & Case approached London with deliberate caution. The firm opened a one-lawyer representative office in London (1946-1952)[10].

Several factors explain the delay between its early post-war representative office and the full opening in 1971.

First, regulatory restrictions in post-war Britain made it nearly impossible for foreign lawyers to practise English law. Under the Business Names Act and the Home Office’s visa rules, non-UK solicitors could only reside in London if they formally undertook not to advise on English law. This meant that an American firm like White & Case could not compete directly in the City’s domestic market.

Second, the post-war economy remained tightly controlled well into the 1950s. Exchange regulations, rationing, and limited transatlantic capital flows left little space for the kind of cross-border finance work that was White & Case’s hallmark.

Third, rather than open prematurely under restrictive conditions, White & Case invested in continental Europe – particularly in Paris (reopened 1960) and Brussels (opened 1967) – waiting until London re-emerged as the global hub of the Eurodollar market in the late 1960s[11].

When the firm finally launched its London office in October 1971, the timing was perfect: the City was opening to international finance, and the regulatory barriers for foreign law firms were beginning to lift.

The Stories We Are Yet to Write

Looking back at how British law firms endured the war years, it is impossible not to see echoes of what Ukrainian firms are facing today.

Across Ukraine, lawyers are now writing their own chapter of professional history. They are working through air raids, rebuilding offices, defending clients and principles under fire – quite literally. Perhaps it is time to start recording these stories, so that one day another generation of lawyers will read them with the same awe and respect with which we now look at London’s legal community of the 1940s.

Because in every era, it is not offices or case files that define a law firm – it is the people who stand their ground when history tests them most.

Acknowledgments

This article was inspired by archival research into the wartime histories of London law firms and the extraordinary resilience of the legal profession during the Blitz. My heartfelt thanks go to all those in London who shared their time and expertise – this piece exists because of them.

Special thanks are due to Edward Fennell, former The Times legal correspondent and founder of The Legal Diary, for his historical perspective; to Nick Mayo and the team at The Law Society for their generous cooperation; to Chris Hale and William Howard (Travers Smith), Katherine Milliken and Liam McCafferty (Macfarlanes), Leah Bassett (CMS UK), Simon Agar (Slaughter and May), and Anand Jeyaram (White & Case) for their guidance and valuable insights.

I also wish to extend my apologies to any firms not mentioned in this article – any omission is entirely unintentional and reflects only the time constraints of the research. Those not named here are no less valued: their stories remain part of the wider history that inspired this work.

[1] Schedule of Reserved Occupations (Provisional: Revision, September 1939). London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1939.

[2] Watkins, Ernest. The Law Society 1939–1945. London: The Law Society, 1947.

[3] The Law Society Annual Reports, 1939–1946. London: The Law Society, 1947.

[4] John J. Magyar. The History of Travers Smith. London: Travers Smith LLP, 2025.

[5] Edward Fennell. The Bird & Bird Story: A History of Two Birds Across Three Centuries. London: Bird & Bird LLP, 2012.

[6] Judy Slinn, Linklaters & Paines: The First One Hundred and Fifty Years. London: Longman Group UK Ltd, 1987.

[7] American Bar Association Journal, “London Letter,” October 1941.

[8] Laurie Dennett, Slaughter and May: A Short History. London: Granta Editions, 1989.

[9] London Metropolitan Archives, LCC/FB/WAR/02/027. Photograph and data © London Metropolitan Archives.

[10] Humphrey Keenlyside, White & Case London: The First Five Decades. London: White & Case LLP, 2018.

[11] Duane D. Wall, White & Case 1901–2016: The First 100 Years & Beyond. New York: White & Case LLP, 2016.